March 24, 2021 will mark a year since the famous west coast wolf known as Takaya was killed by a hunter on Vancouver Island. Two months before his killing winter storms had taken him by strong currents to an urban Victoria community, where he was trapped and relocated to the west coast. In an oddly anthropomorphic statement to the press, the BC Conservation Officer Service declared that the wolf had “left the islands for a reason” to justify not returning him to the islands that he had occupied for eight years. For those who had been following Takaya via local media and a documentary, there was a surety that he would die by a bullet or a trap.

A Freedom of Information request filled in some details about the predictable killing of Takaya. The hunter had been searching for a friend’s lost cougar hounds, missing for days, on Mosaic Forest Management private property near the community of Shawnigan Lake. The wolf that came out of a ditch on a spur road to greet his own dog wore a yellow tag in his left ear.

“He expected the wolf to run off as he had seen them do on many occasions, but instead it stopped on the side of the road and stood there looking at the truck. He knew wolf season was open, so he decided to try to kill it…He is planning on having a taxidermist friend come over and skin the wolf tonight.”

Statistics on wolf kills in the province will not be found in any government data, other than their own aerial killings in an attempt to help disappearing caribou. Hunters are expected to self-report their kills and to stay within “bag limits” of three to no limit within their hunting regions. Equally impossible to quantify is the number of wolves that live in the province, some of whom travel between our borders with the US.

The provincial government relies on the anecdotes of hunters regarding wolf population numbers. It’s unknown how the data from reported wolf kills is compared to the estimated population numbers, if at all. No species license is required to kill wolves, therefore the province has no idea how many hunters are active at any time.

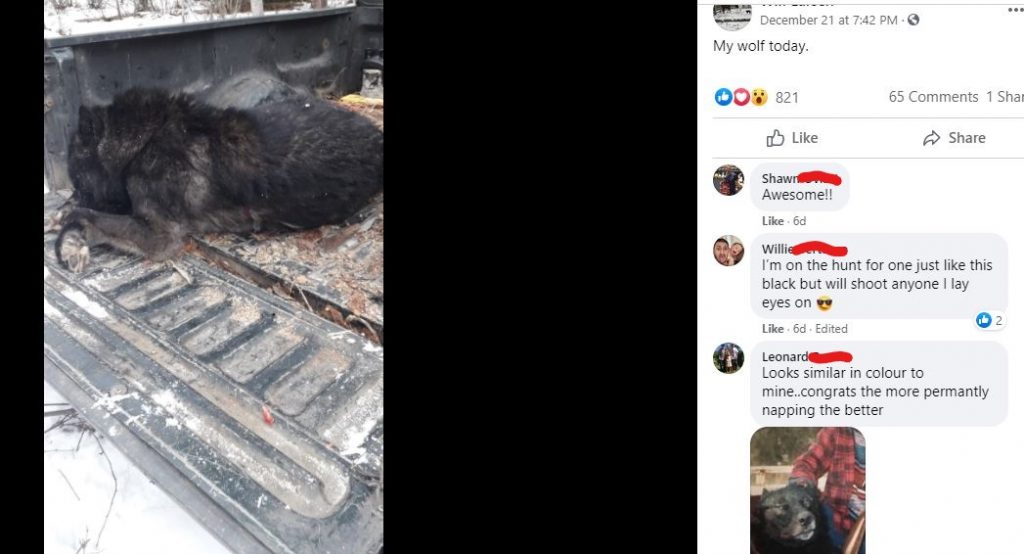

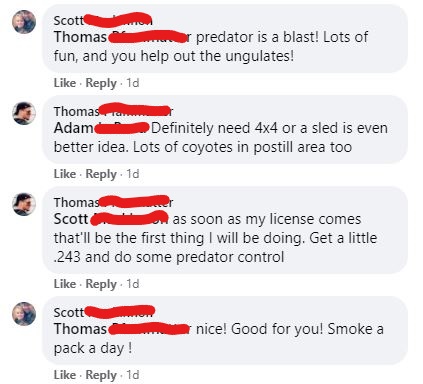

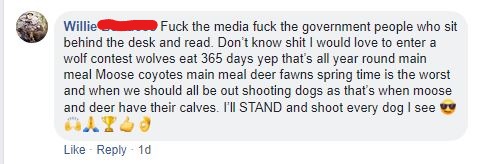

A lack of scientific rigor on the part of the BC government has led to citizen culls of wolves across the province. Motivated by anger towards a species that “competes” with several thousand hunters on the land, many have taken to social media to hate monger and to encourage others to kill every wolf they see, posting graphic photos of their wolf kills.

With her documentary and subsequent book “Takaya, Lone Wolf,” Cheryl Alexander gave the world a new view of a wild wolf. Far from a salivating villain determined to eat everything in his path, Takaya was a remarkably intelligent, resourceful, shy individual who was only curious about the humans and their dogs that he occasionally encountered as he lived out his life on the small Discovery/Chatham Islands, 3 miles east of Victoria, BC.

Hunters and conservation officers alike accused Cheryl Alexander of taming the wolf. Preferring the long-held, and certainly ancient reputation of the wolf as a fearsome killer, they were deliberately deaf to her message that he was an individual who’s life ambition was to simply live. Had he been returned to the islands after the January 2020 storms, it’s certain he would have lived out his days as he had for eight years, living resourcefully from the islands he occupied, safe from hunters and conservation officers due to First Nations protection of the islands.

The life and death of Takaya provided British Columbians with an important lesson. Namely, that our wildlife are not the fairy tale monsters that the hunter narrative portray them to be. They have their own agency, their own niche in ecosystems that we have proven ourselves century after century to have never understood.

By Kelly Carson, December 31, 2021

Recent Comments